order: 4

Interpretation

Once variants have been called, the following steps depend on the type of study and the experimental design. For large population studies, like case-control association analyses, an appropriate large-scale statistical approach will be chosen and different statistical or analytical tools will be used to carry out the tertiary analyses.

When only a few individuals are involved, and in particular in clinical contexts, the goal will be to interpret the findings in light of different sources of information and pinpoint a causative variant for the investigated phenotype.

Overview

When variants have been called, and a diagnosis is necessary, investigators will need to combine:

- the predictions resulting from annotations like the one we carried out

- biological and clinical information

with the goal of narrowing the search space and reducing the number of variants to be inspected. This approach is summarised in the diagram below:

Once the list of variants has been reduced, more in-depth analyses of the reported cases and the genomic region in existing databases might be useful to reach a conclusion.

Finding Causative Variants

Some of these steps might be carried out via software. For this tutorial however, we chose to perform these steps one by one in order to get a better view of the rationale behind this approach.

We will start by looking at the annotated VCF, which is found at this location in our GitPod environment:

cd /workspace/gitpod/training/annotation/haplotypecaller/joint_variant_callingHere, we should verify in which order the two samples we used for this analysis have been written in the VCF file. We can do that by grepping the column names row of the file, and printing at screen the fields from 10th onwards, i.e. the sample columns:

zcat joint_germline_recalibrated_snpEff.ann.vcf.gz | grep "#CHROM" | cut -f 10-This returns:

case_case control_controlshowing that case variants have been written in field 10th and control variants in field 11th.

Next, in this educational scenario we might assume that an affected individual (case) will carry at least one alternative allele for the causative variant, while the control individual will be a homozygous for the reference. With this assumption in mind, and a bit of one-liner code, we could first filter the homozygous for the alternative allele in our case, and then the heterozygous.

In this first one, we can use the following code:

zcat joint_germline_recalibrated_snpEff.ann.vcf.gz | grep PASS | grep HIGH | perl -nae 'if($F[10]=~/0\/0/ && $F[9]=~/1\/1/){print $_;}'which results in the following variant.

chr21 32576780 rs541034925 A AC 332.43 PASS AC=2;AF=0.5;AN=4;DB;DP=94;ExcessHet=0;FS=0;MLEAC=2;MLEAF=0.5;MQ=60;POSITIVE_TRAIN_SITE;QD=33.24;SOR=3.258;VQSLOD=953355.11;culprit=FS;ANN=AC|frameshift_variant|HIGH|TCP10L|ENSG00000242220|transcript|ENST00000300258.8|protein_coding|5/5|c.641dupG|p.Val215fs|745/3805|641/648|214/215||,AC|frameshift_variant|HIGH|CFAP298-TCP10L|ENSG00000265590|transcript|ENST00000673807.1|protein_coding|8/8|c.1163dupG|p.Val389fs|1785/4781|1163/1170|388/389|| GT:AD:DP:GQ:PL 1/1:0,10:10:30:348,30,0 0/0:81,0:81:99:0,119,1600Now we can search for this variant in the gnomAD database, which hosts variants and genomic information from sequencing data of almost one million individuals (see v4 release).

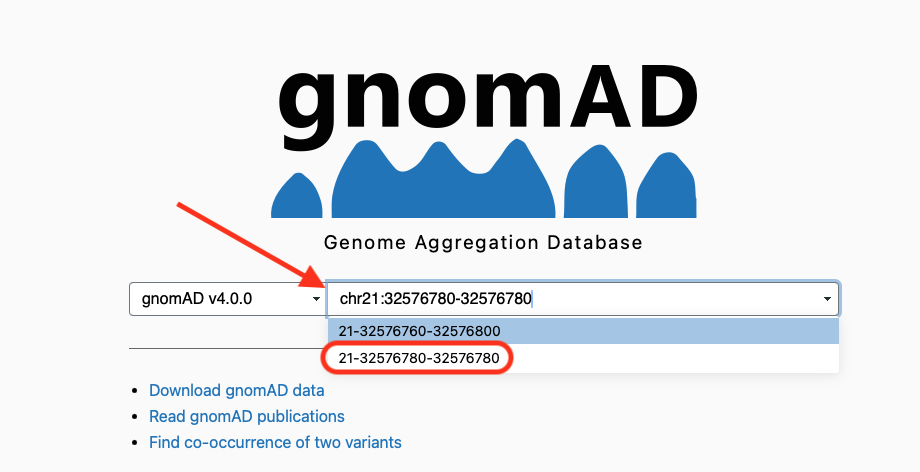

In order to search for the variant we can type its coordinates in the search field and choose the proposed variant corresponding to the exact position we need. See the figure below:

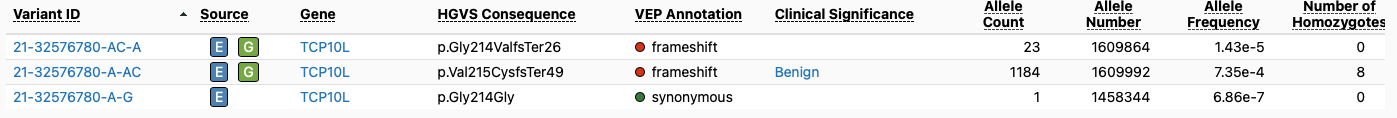

the resulting variant data show that our variant is present, and that it’s been described already in ClinVar, where the provided interpretation (Clinical Significance) is “Benign”.

We can see the resulting table in the following image:

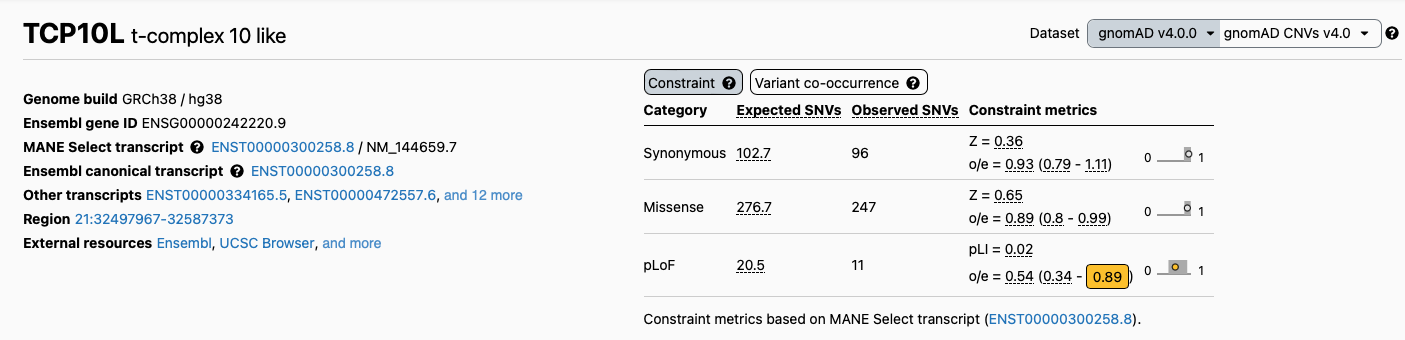

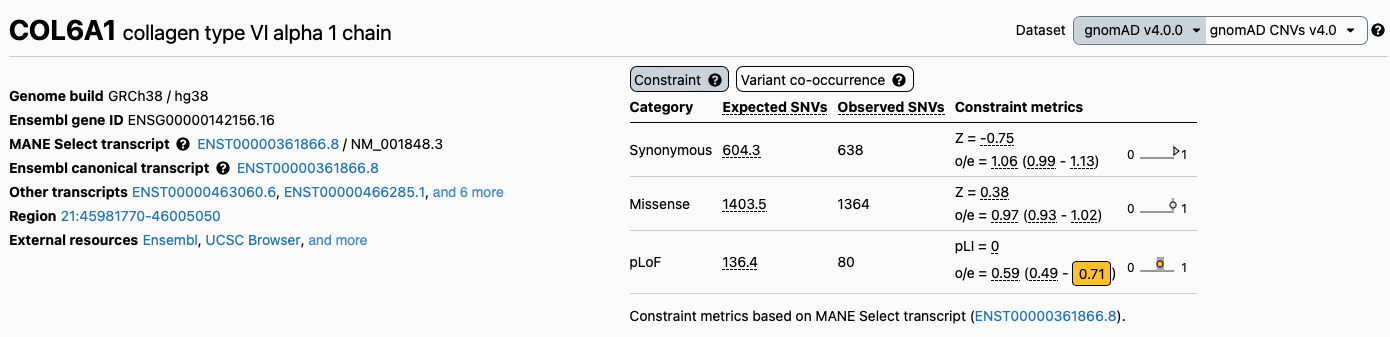

Quite importantly, the gnomAD database allows us to gather more information on the gene this variant occurs in. We can inspect the so called “constraint data”, by clicking on the gene name and inspecting the “constraint” table on the top right of the page.

This information gives us a better view of the selective pressure variation on this gene might be subject to, and therefore inform our understanding of the potential impact of a loss of function variant in this location.

In this specific case however the gene is not under purifying selection neither for loss of function variants (LOEUF 0.89) nor for missense ones.

We can continue our analysis by looking at the heterozygous variants in our case, for which the control carries a reference homozygous, with the code:

zcat joint_germline_recalibrated_snpEff.ann.vcf.gz | grep PASS | grep HIGH | perl -nae 'if($F[10]=~/0\/0/ && $F[9]=~/0\/1/){print $_;}'This will results in the following list of variants:

chr21 44339194 rs769070783 T C 57.91 PASS AC=1;AF=0.25;AN=4;BaseQRankSum=-2.373;DB;DP=84;ExcessHet=0;FS=0;MLEAC=1;MLEAF=0.25;MQ=60;MQRankSum=0;POSITIVE_TRAIN_SITE;QD=3.41;ReadPosRankSum=-0.283;SOR=0.859;VQSLOD=198.85;culprit=FS;ANN=C|start_lost|HIGH|CFAP410|ENSG00000160226|transcript|ENST00000397956.7|protein_coding|1/7|c.1A>G|p.Met1?|200/1634|1/1128|1/375||,C|upstream_gene_variant|MODIFIER|ENSG00000232969|ENSG00000232969|transcript|ENST00000426029.1|pseudogene||n.-182T>C|||||182|,C|downstream_gene_variant|MODIFIER|ENSG00000184441|ENSG00000184441|transcript|ENST00000448927.1|pseudogene||n.*3343T>C|||||3343|;LOF=(CFAP410|ENSG00000160226|1|1.00) GT:AD:DP:GQ:PL 0/1:8,9:17:66:66,0,71 0/0:67,0:67:99:0,118,999

chr21 44406660 rs139273180 C T 35.91 PASS AC=1;AF=0.25;AN=4;BaseQRankSum=-4.294;DB;DP=127;ExcessHet=0;FS=5.057;MLEAC=1;MLEAF=0.25;MQ=60;MQRankSum=0;POSITIVE_TRAIN_SITE;QD=0.51;ReadPosRankSum=0.526;SOR=1.09;VQSLOD=269.00;culprit=FS;ANN=T|stop_gained|HIGH|TRPM2|ENSG00000142185|transcript|ENST00000397932.6|protein_coding|19/33|c.2857C>T|p.Gln953*|2870/5216|2857/4662|953/1553||;LOF=(TRPM2|ENSG00000142185|1|1.00);NMD=(TRPM2|ENSG00000142185|1|1.00) GT:AD:DP:GQ:PL 0/1:48,22:71:44:44,0,950 0/0:51,0:51:99:0,100,899

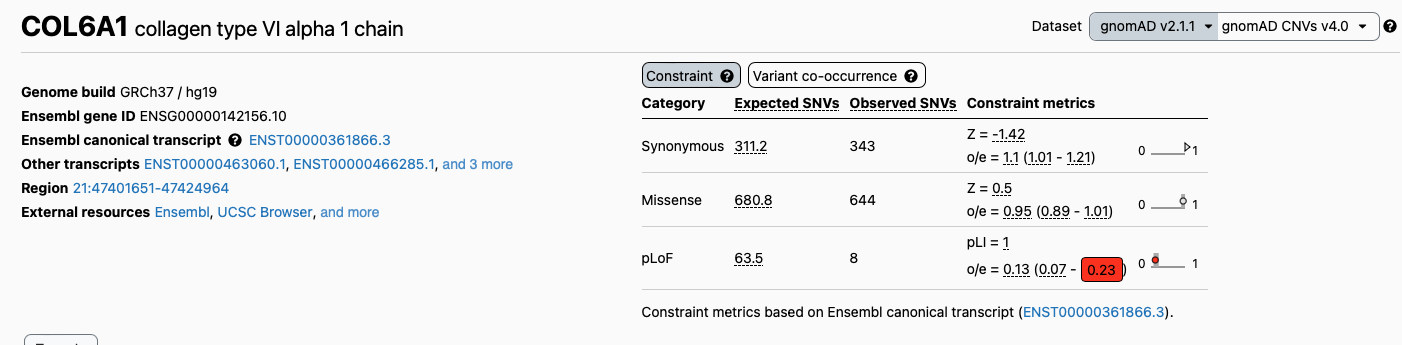

chr21 45989090 . C T 43.91 PASS AC=1;AF=0.25;AN=4;BaseQRankSum=2.65;DP=89;ExcessHet=0;FS=4.359;MLEAC=1;MLEAF=0.25;MQ=60;MQRankSum=0;QD=2.58;ReadPosRankSum=-1.071;SOR=1.863;VQSLOD=240.19;culprit=FS;ANN=T|stop_gained|HIGH|COL6A1|ENSG00000142156|transcript|ENST00000361866.8|protein_coding|9/35|c.811C>T|p.Arg271*|892/4203|811/3087|271/1028||;LOF=(COL6A1|ENSG00000142156|1|1.00);NMD=(COL6A1|ENSG00000142156|1|1.00) GT:AD:DP:GQ:PL 0/1:10,7:18:51:52,0,51 0/0:70,0:70:99:0,120,1800If we search them one by one, we will see that one in particular occurs on a gene (COL6A1) which was previously reported as constrained for loss of function variants in the database version 2.1:

while the version 4.0 of the database, resulting from almost one million samples, reports the gene as not constrained:

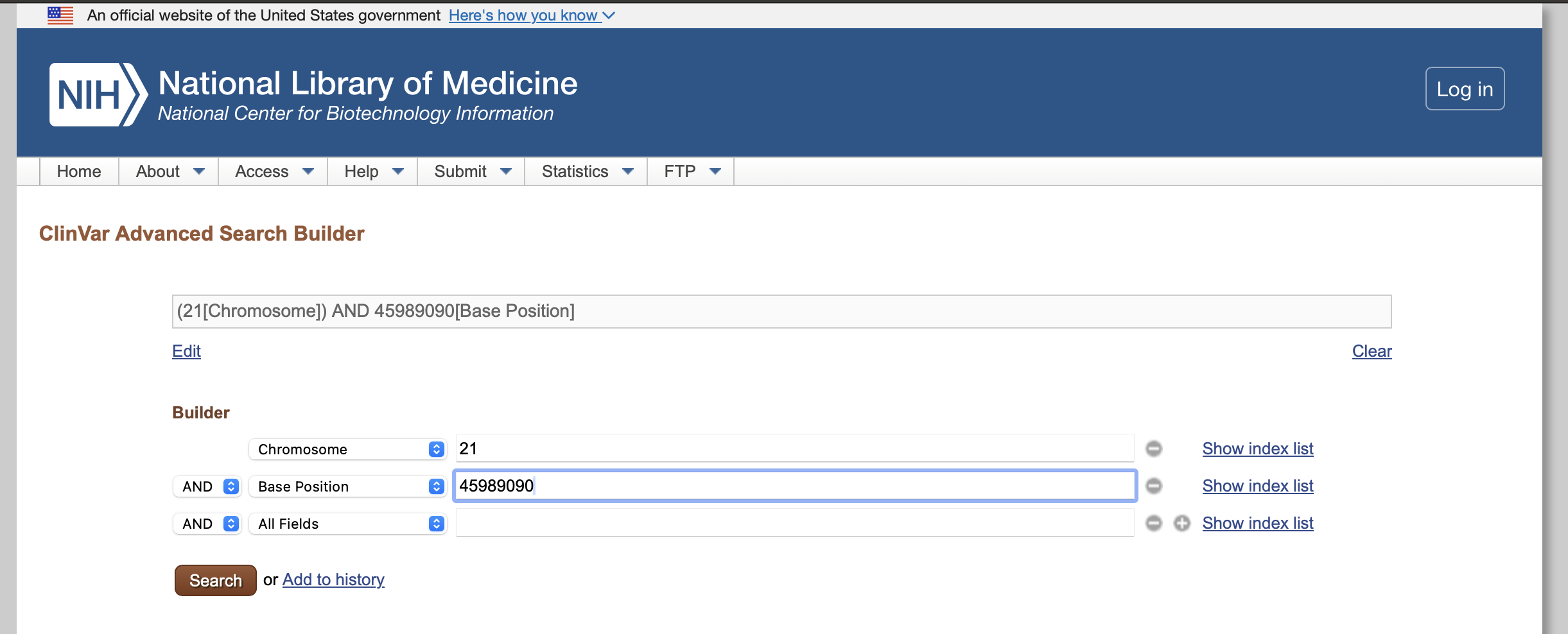

We can search for this variant in ClinVar by using an advanced search and limiting our search to both chromosome and base position, like indicated in figure below:

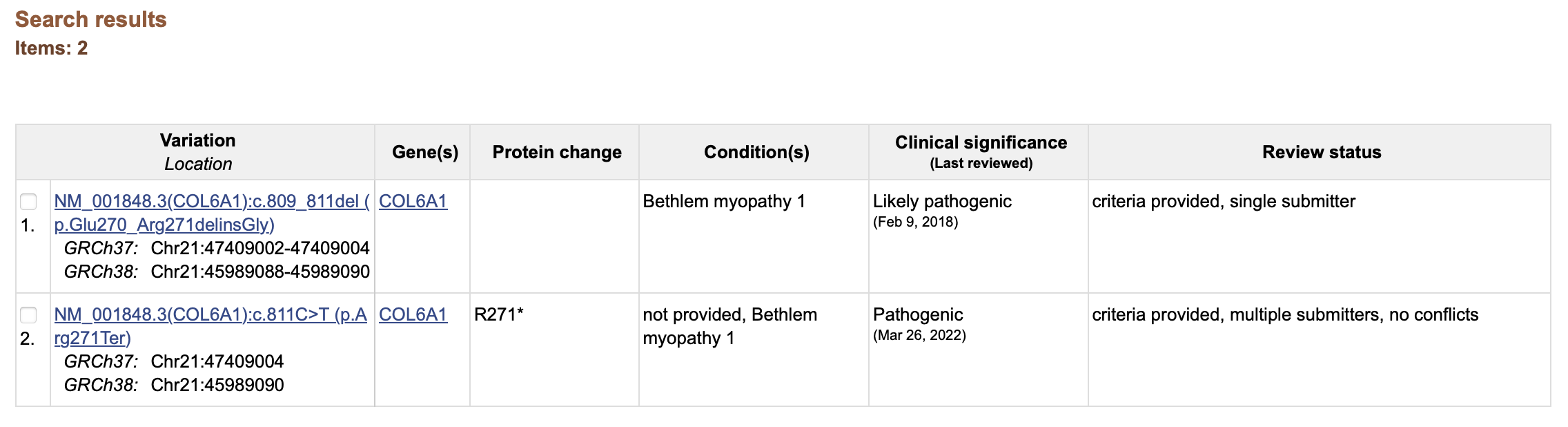

This will return two results: one deletion and one single nucleotide variant C>T corresponding to the one we called in the case individual:

If we click on the nomenclature of the variant we found, we will be able to access the data provided with the submission. In this page we can see that multiple submitters have provided an interpretation for this nonsense mutation (2 stars). Under the section “Submitted interpretations and evidence” we can gather additional data on the clinical information that led the submitters to classify the variant as “pathogenic”.

Conclusions

After narrowing down our search and inspecting genomic context and clinical information, we can conclude that the variant

chr21 45989090 C T AC=1;AF=0.25;AN=4;BaseQRankSum=2.37;DP=86;ExcessHet=0;FS=0;MLEAC=1;MLEAF=0.25;MQ=60;MQRankSum=0;QD=2.99;ReadPosRankSum=-0.737;SOR=1.022;VQSLOD=9.09;culprit=QD;ANN=T|stop_gained|HIGH|COL6A1|ENSG00000142156|transcript|ENST00000361866.8|protein_coding|9/35|c.811C>T|p.Arg271*|892/4203|811/3087|271/1028||;LOF=(COL6A1|ENSG00000142156|1|1.00);NMD=(COL6A1|ENSG00000142156|1|1.00) GT:AD:DP:GQ:PL 0/1:8,6:15:40:50,0,40 0/0:70,0:70:99:0,112,1494is most likely the causative one, because it creates a premature stop in the COL6A1 gene, with loss of function variants on this gene known to be pathogenic.